Open For Business: The 1970s

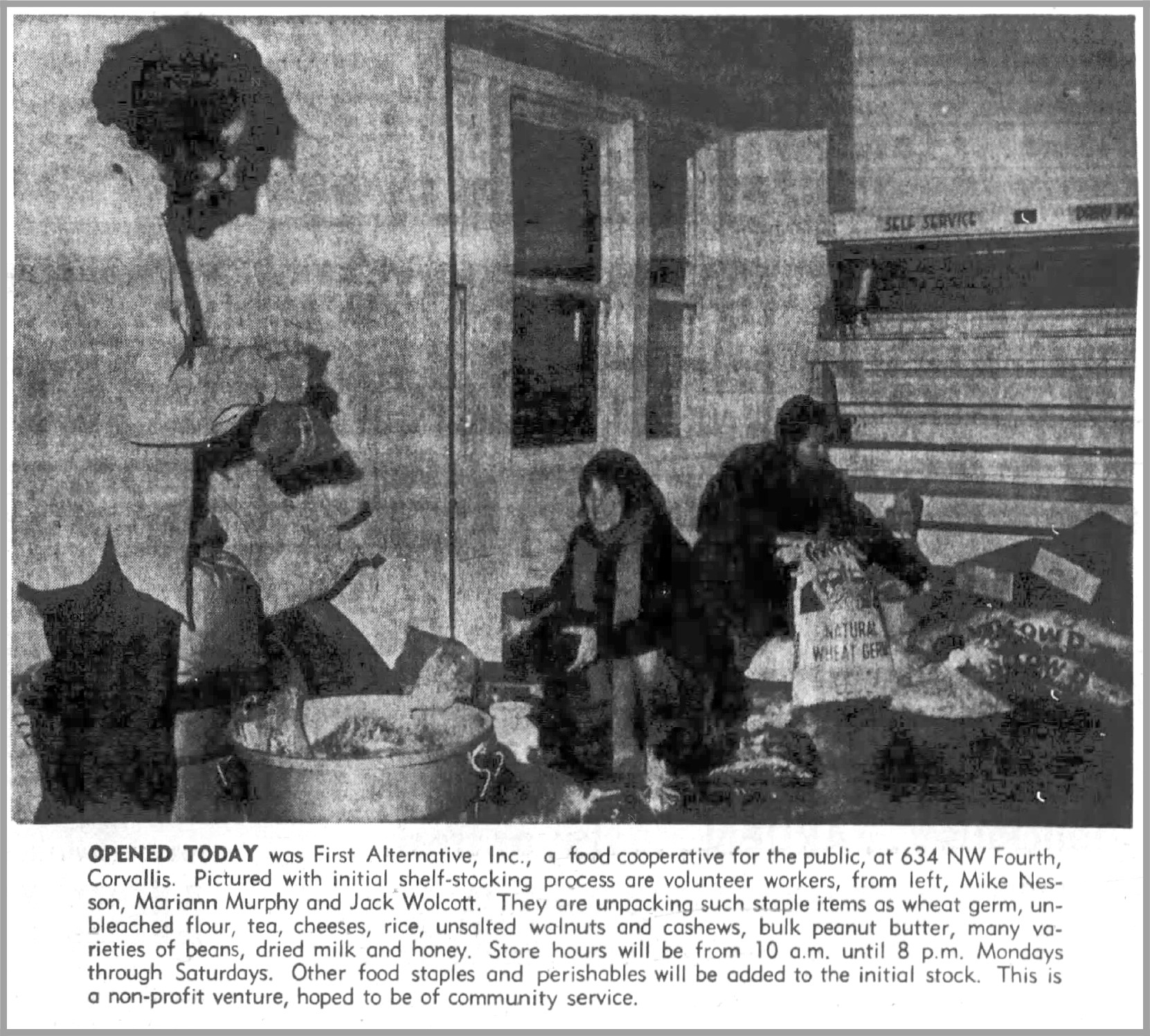

Opening day was November 23, 1970. Corvallis’s newest grocery store was well-scrubbed, if not well-stocked…

“I think there were three burlap sacks—one each of beans, wheat and rice—in the little 10 x 10-foot grain room,” recalled early volunteer Mike Nesson, “their sides rolled down for easy scooping.”

“That was in what had been a downstairs bedroom,” added Joyce Nesson, Mike’s wife and another volunteer.

“The other bedroom became the cheese room.” Don Marquis, one of the first managers, said, “I think later a small produce cooler stood against the back wall of the main room.” He also recalled that most of the produce came from people’s gardens.

Mary Lou Magers worried about the wheat germ, kept in a dark closet since refrigeration was limited. Peggy McKimmy donated an old refrigerator from her garage. Hildred Rice remembered a dirt-floor basement where a freezer held honey ice cream from California. She also remembered how hot the house got in summer.

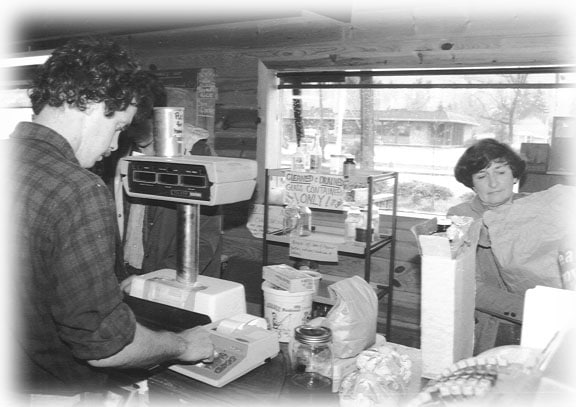

No one was in a hurry when they shopped, according to McKimmy. “We were all learning and the old cash register was big and slow, so if you were in a hurry you didn’t shop there. But there was a friendliness that didn’t exist elsewhere.”

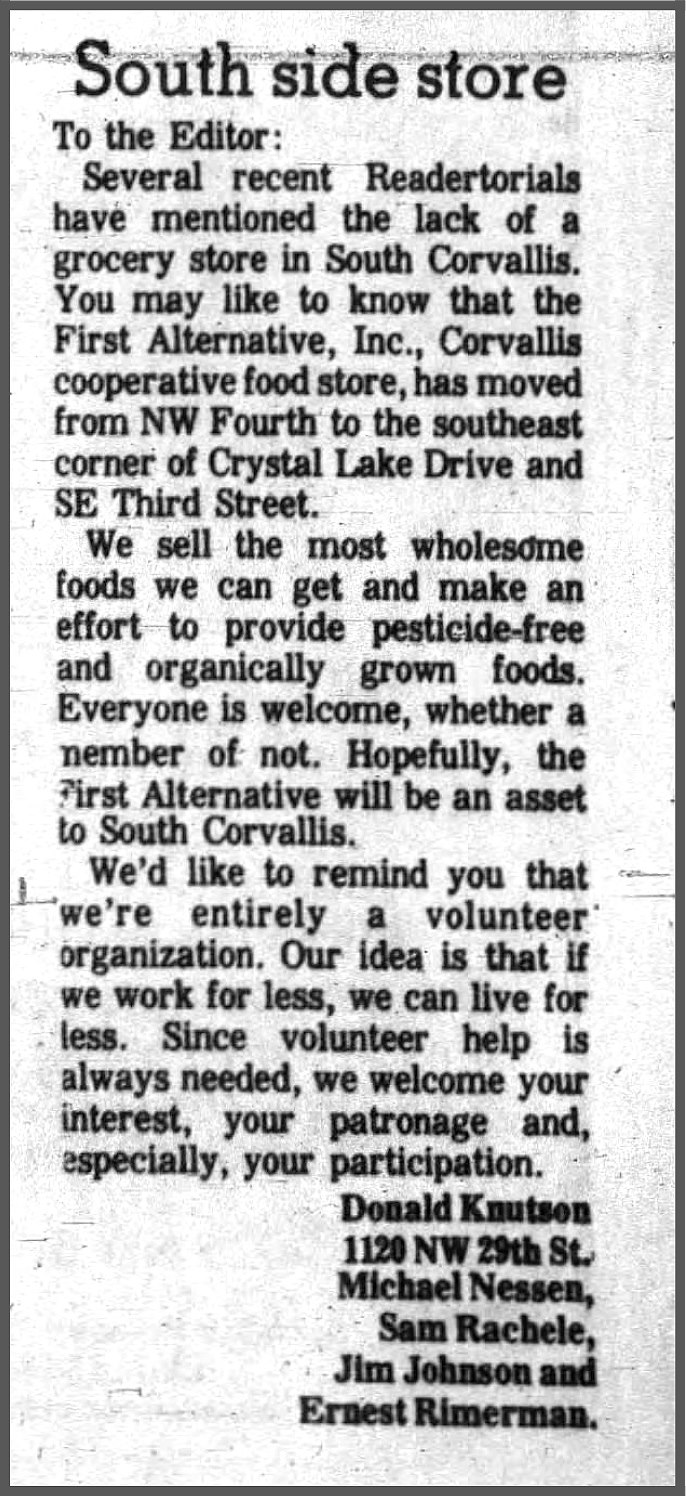

Gene Newcomb remembered the house being small, cramped and gray. “The building we’re in now seems so grand by comparison, with all its windows,” he said of the south store in a 1990 interview.

Rose Marie (Nichols) McGee appreciated the “breadth of ages” she encountered at First Alternative. Her husband, Keane, traveled to Salem for goods from a wholesale foods outlet. “If the Co-op couldn’t sell something cheaper than other stores,” she said, “we didn’t carry it.” She and her sister Gloria helped launch the herb section. Because their parents owned Nichols Garden Nursery in Albany, they were able to buy herbs through the nursery’s distributors.

McGee also felt Co-op members were special because they acted on moral beliefs, listing senior discounts, the children’s play area, and how they handled a street person who became a “heavy grazer.”

“Rather than confront him, we looked at what we could do to help him.” Don Marquis remembered that as the start of the Free Soup Pot. “We made it out of marginal produce and miso. It was both practical—so we wouldn’t lose a lot of food—and compassionate: we wanted to feed the truly hungry.”

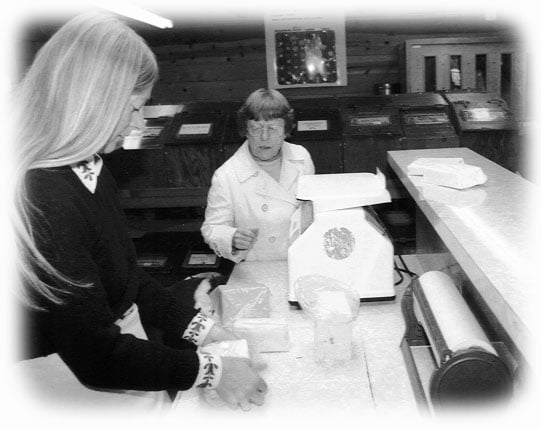

Margo Denison remembered going to shop and being greeted with a broom. “Whoever was in charge that day said, ‘I’m not going to open this place until it gets cleaned up. Do you want a broom?’” Margo swept. Her shopping excursions were frequently extended by stints at the cheese counter. “As a teacher, I’d had a tuberculosis test, which was also required for a food handler’s permit in those days. Sometimes I was the only one in the store qualified to cut cheese.”

It may have been Joyce Nesson who handed Margo the broom. “Sometimes whoever was responsible for cleaning up didn’t do it, so some of us refused to open until the job got done. Those who came from a long way and found us closed weren’t too pleased, but we felt it was necessary.”

Many of the original members found themselves putting in far more than the standard two hours a week. Jack Wolcott, co-owner of Grass Roots Bookstore today, was a student then who tried, for the sake of his studies, not to get too involved at first. “Soon I was going to class only for tests,” he admitted. “I was learning so much at the Co-op and was gaining a lot of self-esteem. I found there was something better to do than just work for a living, that you could have value in what you did.”

Mike Nesson was often called from his lab at OSU to write a check for a supplier. “I intended to get right back to the lab, but often a trip at 10 am lasted until 4 or 5 pm. I obviously enjoyed being there more than at school.”

Denis DeCourcey, an early manager who later moved to Portland, was heavily involved for several years. “The Co-op provided very real spiritual nourishment for me,” he said. “I think it’s been that way for a lot of others too. People would come to shop, but knew they’d see someone they wanted to talk to, as well. Being in the middle of that in the heady days of the early-to-mid-1970s was really great. As a manager who spent most of my time there, I was in touch with everybody. I felt mine was a very privileged position in a very privileged spot.”

“It was probably the Co-op that taught us that we could do unexpected things,” said Joyce Nesson. “The mystique of the business world was totally stripped away and we learned we were capable, competent people. We found personal power as well as group power.”

Recollections of the earliest days of First Alternative, gathered and presented by Chris Peterson, Thymes contributor since 1984