How It All Began

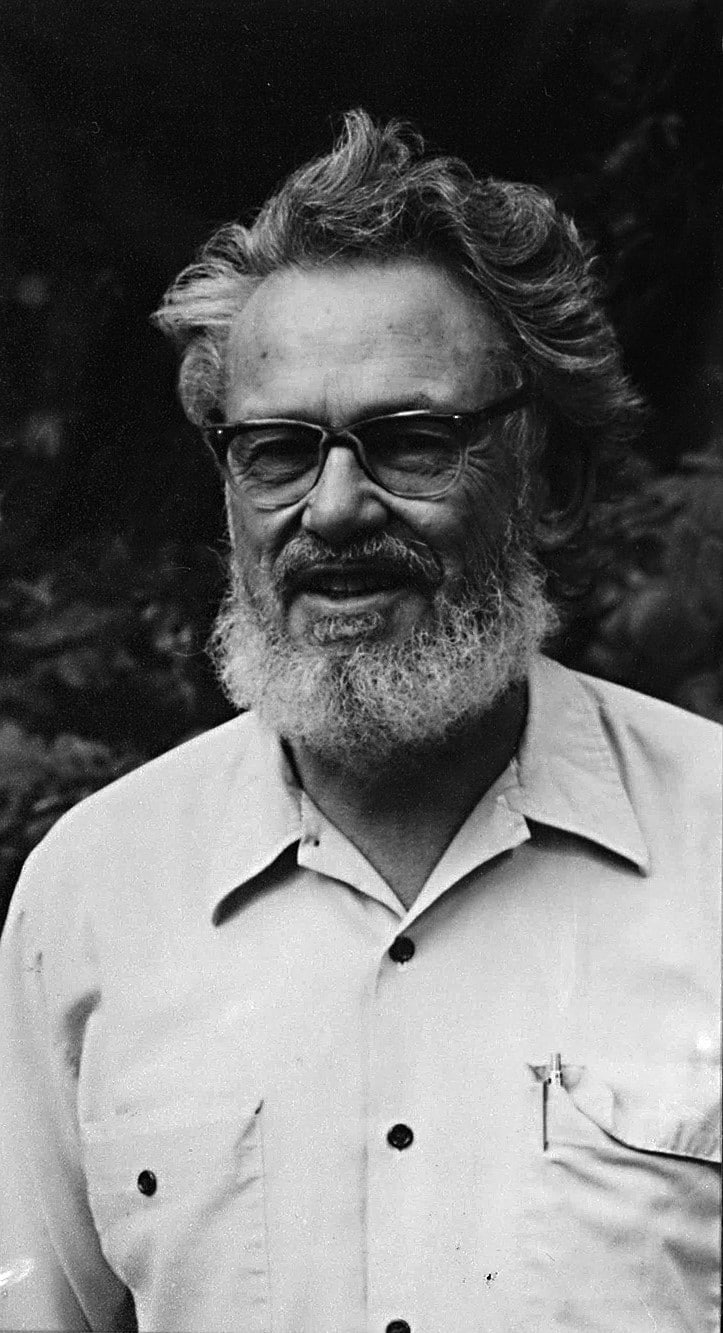

In the late 60s a handful of OSU students with Associate Professor of Botany Dr. William Denison as their faculty advisor wanted to start a cooperative grocery store. “Co-ops were the coming thing on the west coast at that time,” Denison said in an interview around the turn of the century. “There was one in Eugene, one in Portland, and one in Seattle, as well as food conspiracies and collective buying groups in other parts of the country.” The students wanted a place to buy things that weren’t available elsewhere in town, especially bulk items and whole grains. In his business travels up and down the coast, Denison visited co-ops for ideas and advice. In town, word spread beyond campus. An interesting mix of backgrounds, professions and ages showed up at organizing meetings.

Peggy McKimmy, then a young wife and mother, described the motley group of students, alternative types, housewives and professionals best: “We were unlikely soul mates brought together through a common interest. I found I really liked the interaction with people who looked a lot different from each other on the outside, but who found that, on the inside, they cared about the same things. We probably never would have begun to communicate otherwise. But here it didn’t matter what you looked like. Families were welcome. It wasn’t just women, or just men, or just students. Everyone was accepted and accepting. I learned so much about new ways of eating. We had regular potlucks—wonderful potlucks. That’s where I learned about vegetarian foods. For me, it was a true adventure.”

Hildred Rice, one of the more senior members attending the first meetings, recalled a notice about a meeting or fund-raising dinner at OSU’s Memorial Union. “When these people began talking about starting a grocery store, I thought they were crazy. What did they know about a grocery store? Well, I found they’d given it a lot of thought and had formed committees to look for a building and find food for the store. The goal from the very beginning was to provide healthful, nourishing food at good prices—and still is,” she said.

By early 1970, First Alternative had incorporated—not as a true cooperative, but as a non-profit corporation. Meanwhile, the building committee was having trouble finding an affordable place. Rents in the preferred downtown area were out of reach. Finally, in August 1970, a realtor located a wood frame house on NW 4th Street. “It was an enormous relief,” Denison recalled.

It took a lot of work to turn the house into a store, but the group became a humming machine in the process, fueled by enthusiasm and sheer determination to turn their dream into “the Co-op.” Folks began making food runs to Eugene, Salem, Portland, and even as far as Vancouver, B.C. and San Francisco.

But, energy and enthusiasm weren’t legal tender for paying bills and money was still scarce. A community donation of $500, enough to cover rent for two months. “That made a big difference,” said Michael Nesson, a key organizer and post-doc at OSU at the time. “It allowed us to concentrate on getting the store running without having to worry about fund-raising for the moment.” They scraped together more capital by selling $25 and $100 promissory notes, and asking members to pre-pay their grocery bills. Credit accounts were kept on 3×5 note cards stored in a metal box.

“First Alternative’s initial supplier was the Willamette People’s Co-op in Eugene,” Nesson said. “We didn’t have the capacity even to buy a full sack of grain at first. Several of us would go to Eugene in the evening, after their Co-op closed, and they’d allow us to shop for our store. First Alternative had a straight ten percent mark-up and we calculated we’d have to sell our entire inventory ten times each month just to come up with expenses.” And they did just that, thanks not only to all-day volunteer efforts inside the store, but to volunteer food runs up and down the valley. Eventually, suppliers and distributors decided the fledgling business was stable enough to add to their delivery routes.

“It was a very political act, even for such a diverse group,” said Joyce Nesson, who joined the group with her husband, Michael, at the second meeting. “We were taking control—seizing economic power—over what we bought and from whom we bought the things necessary to sustain the most basic human need: for food. It was telling the status quo, ‘thank you, but we’ll do this ourselves.’ We were surely fueled by the various boycotts of that era, but our politics were even broader than that. It was the old American grass roots doing it and I think some of us were startled by just how much power we could take.”

William Denison’s son Tom would soon be one of the first to sell locally grown produce at the Co-op. Tom recently retired. To read more about his contributions to the Co-op and the community, read the Summer 2020 Thymes

Adapted from an article by Chris Peterson, Thymes contributor since 1984